"Jack Be Nimble"--Jack O'Brien's Resurrection of Ellis Rabb

|

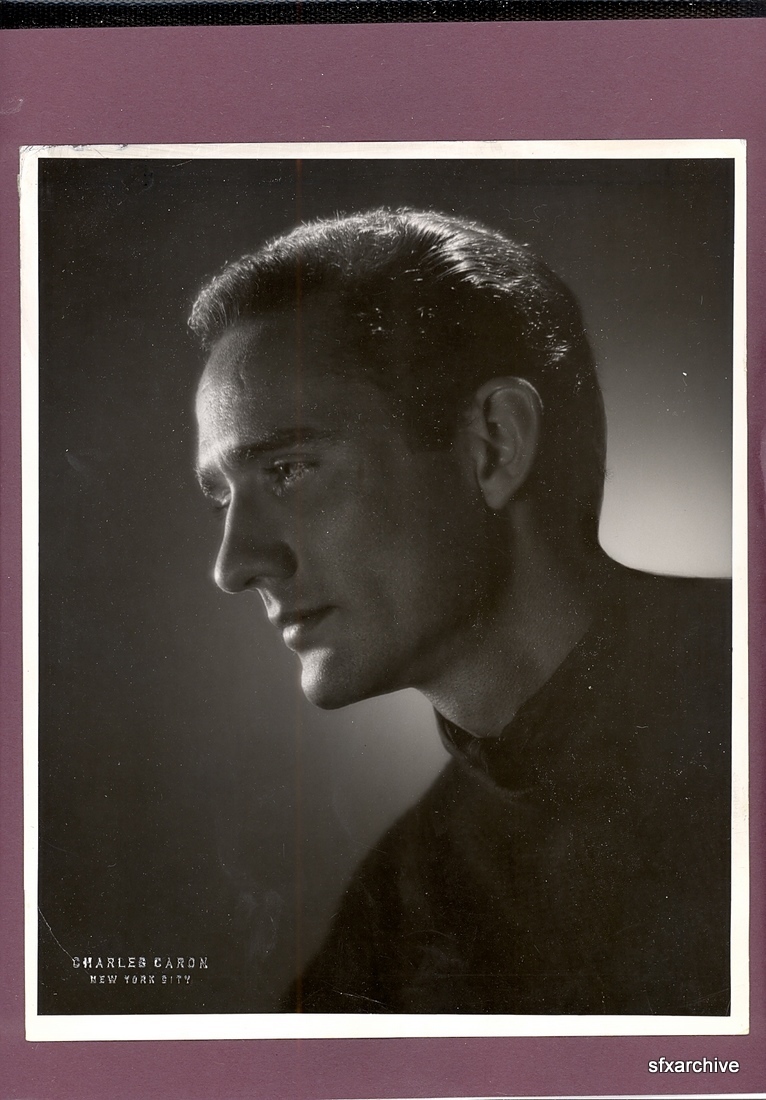

| Ellis Rabb, by Charles Caron |

In 1992, in a moment of ambition and

insanity, the actress Carrie Nye introduced me to the director Ellis Rabb and

offered me as an assistant. “We need to resurrect Ellis,” Nye drawled, and I

accepted—briefly—the assignment. I did not—could not—know that the resurrection

of Rabb was an annual, perhaps daily, ritual among his acolytes and friends,

and that the tasks had been performed, like the Stations of the Cross, for

thirty years. Rabb was a dysfunctional, charismatic ruin, but many people kept

trying—with little success—to prop him up on a pedestal and light candles

beneath his feet.

The task at hand was a revival of Paul

Osborn’s Morning’s at Seven, which

was to be produced by a new iteration of the Association of Producing Artists

(APA), the company that Rabb had founded in the 1960s, and it was to be mounted

at the State University of New York at Purchase. Rabb was in no condition at

the time to dress or feed himself, and his ears throbbed with the pain of Ménière's

disease,

but he was going to reclaim his position in the theatre, and he soon cast his

play with a retinue of supplicants from his past. Within a matter of days, I

realized that Rabb had no intention of directing anything: He simply got his

friends together and left them to their own devices in a play sweet and

sentimental, onto which he grafted cute and showy effects: Glitter on garbage.

I also realized that my primary responsibilities were to keep Rabb stocked with

vodka and to tend to the tiny dog of Meg Mundy.

I resigned.

Carrie Nye invited me over, hugged me, and

said, with some regret, that this was how Ellis had always worked (“although

drier at times,” she admitted), and that I might have waited a bit longer for

some magic to fall upon me. “Ellis has an alchemy about him,” she told me, but

I never saw it. Many did—none as clearly, as fervently, as Jack O’Brien, who

has written an autobiography entitled “Jack Be Nimble”(Farrar, Straus and

Giroux; $35) which is, in reality, a hagiographic tract for Ellis Rabb,

reverent and glossy with myth.

To read, review, or fully understand “Jack

Be Nimble,” one must look upon it as a pilgrim’s progress, with a heavy

religious scent hanging over it, like a fart in a green room, in which a young

rube from Michigan, eager and positive, falls beneath the spell of an exotic,

beguiling older man—a flawed holy father-- who teaches him secrets and nostrums,

miracles and intercessions. Ellis Rabb evoked a priapic, near-sighted stork,

manic and hyperbolic, offering endless pronouncements and announcements of new

productions, new ideas, or his imminent death. He was forever in need of either

an entrance cue or medical intervention, and he was given far too many of the

former.

Rabb’s credo—which he shared generously—was that

one should and must become indispensable to someone very quickly, by doing

anything and everything to earn a niche from which to learn, to steal, to

shine. Rabb was a director of effects and absolutely no introspection, and his

addiction to nostalgia and Americana (he firmly believed that audiences needed

and deserved a revival of “You Can’t Take It With You” every year or two,

preferably as perceived by him) led to diminishing returns, a magician pulling mangy rabbits from a stained hat. One left

Rabb productions humming the sets and the curtain calls, and enjoying the

attempts from the company to evoke the past, as if they had gone without sleep watching

black-and-white movies and studying adjectival acting. But Rabb, despite his

dependence on effects, admitted to me that each play had to have a creamy

nougat center, a pearl of great price if you will, and the success of his 1975

revival of “The Royal Family” was attributable to his securing the services of

Eva Le Gallienne to anchor the play, to shine as a historical memento, to give

it a weight it never possessed. Rabb also directed Rosemary Harris (from whom

he was then divorced) to whip up a malignant meringue of a performance—airy and

manic and reminiscent of nights when they argued and Rabb ran away to spend nights

in the arms of various men. Play therapy with lavender gels. Presented during

the country’s Bicentennial pageantry, it was presented and accepted as a holy

relic of sorts—the finger bone, perhaps, of Saint Ann—and was loudly applauded.

It was the highlight of Rabb’s career, and, upon accepting his Tony Award for

direction, he announced that the APA was coming back. It never did, but Rabb

spent the remainder of his career, such as it was, hauling out his revivals,

cast with his retainers, drinking, and driving away all but the most loyal.

(Proof that Rabb’s ministrations mattered was the recent revival of “The Royal

Family,” which was a soufflé whose primary ingredient was pig iron.)

|

| Eva Le Gallienne and Rosemary Harris in Ellis Rabb's The Royal Family (1975) |

After many years and several hundred pages

of utter idolatry and concern for Rabb, O’Brien finally breaks with him, and

achieves his independence by firing Rabb from a play he was directing. This

could be said to be O’Brien’s Martin Luther moment, his act of boldness the

nailing of theses to a door he now closes on Rabb, and one hopes that the next

installment from O’Brien (“Jack Be Quick,” I would imagine, as he makes up for

lost time and innocence) will deal with his work for the past thirty years.

All autobiographies are confessions, and if

they are good, and this one is, they also throw light on the lies that have

been living in the corners, and that is what O’Brien has done here. He does not

discount or dismiss Ellis Rabb—nor should he—but he separates the wheat from

the chaff and can now see what should not be done. O’Brien has been more daring

than Rabb in his choices—he has not been dependent on revivals, and he

successfully operated a theatre, the Old Globe, in San Diego, and he has

retained his friends—and, like Rabb, he is a director known for sweeping effects,

but, unlike Rabb, he holds actors securely in both his palm and in his plays.

More than a dozen actors have told me that they never feel safer than when they

are directed by Jack O’Brien. The wonder of O’Brien’s talent and influence is

revealed when one reads Tom Stoppard’s “The Coast of Utopia,” a trilogy of

chloroform, and realizes that what moved you at all was provided by O’Brien: It

is not in the pages. For a man who is as passionate about and loving of the

theatre as O’Brien is, it cannot be terribly satisfying to have in his credits such

productions as “The Full Monty,” “Hairspray,” “Catch Me If You Can,” and two

horrors known as “Impressionism” and “Dead Accounts,” the latter two making me

worry that he was facing problems with a mortgage or a malignancy: There are no

other reasons for him to accept such assignments, until I read in these pages

that directors never really retire (O’Brien is now in his seventies) and that

he is a man who wants very much to remain active, alive, necessary. His talent

deserves better material, but greater men than I will have to write a shelf

full of books to tell us where this material might be, or if it will be

received by anyone.

Several years ago I began—and ultimately

abandoned—a book that would deal with the art of directing. I had interviewed

hundreds of actors, designers, and playwrights, and had asked them to define

for me what made a good director. It was a fascinating period of time, and Jack

O’Brien’s name repeatedly was mentioned, and from those both working in the

current theatre and those who once had and who now studied it with an

appreciative distance, including Elia Kazan and Arthur Penn.

What so many people love and admire—and always,

always notice—about O’Brien’s work is that each production is a sort of flag

planted firmly and lovingly in the timeline of theatre history, and the

audience and the actors sense where they stand and why it matters (if it does)

and why it is being done. Jack O’Brien is very much a director who loves the

theatre and knows its place, even if most working with him do not, so he is, as

Penn put it, something of a mystic, a wise man determined to let us know why

things should matter and be remembered. To watch a play directed by O’Brien is

to discover what he has learned, discarded, implanted into his work, and to

read “Jack Be Nimble” is to watch him boldly walk toward his dream, embrace it,

watch it curdle, and then present it as a cautionary tale. He got out of it

alive, and he told the truth. The years of the APA were a maze of mendacity and

gauze, and over the entire enterprise was a victim mentality that was fueled

regularly by Rabb and Harris: Rabb was always on the precipice of a breakdown

or foreclosure, and Harris, who always maintained that Rabb’s homosexuality was

a complete surprise and betrayal to her, kept everyone aware of their bravery

and their errant dreaming. “This we do for you,” they seemed always to be saying,

according to Uta Hagen, who came to the APA in 1968, and found it worth doing

but, as she put it, “a company with no foundation, a leaking roof, and an attic

full of rabid bats.”

Rabb enjoyed regaling people with tales of

how hard he worked and how little appreciation he received, and Harris liked to

tell fellow actresses that she could not understand how Ellis, a man who

compared her perky, pink nipples to flawless roses, could not and would not

give her a child. These are people who were unfamiliar with the truth and never

tried too hard to uncover it. The reality of the situation, as Carrie Nye

believed it, is that they both got what they wanted, with concomitant pain,

damage, and bruised accomplices. Rabb made Harris a star, taught her how to

dress and move and read plays. Harris was the compliant doll upon which Rabb

could affix designs and motives. O’Brien also got what he wanted, but he is the

only member of this particular trinity to admit as much, and it would take a

particularly dishonest reader to not admit that we all lie as often and as

extravagantly to survive and function, especially in what is left of the

American theatre.

When it became apparent, in 1992, that I

could offer no aid to Ellis Rabb as a directorial assistant, we would still

meet for lunch and talk about things. Rabb was always writing plays—big and

bold and always with a woman offering rescue—and he wanted me to read some

pages he had crafted of an autobiography. Rabb would order a Salty Dog (Le Gallienne’s

favorite drink) and he would tell stories about the joy of living in a

perpetual fantasy of what the theatre might become. These were fascinating

stories, and they would send a person out in the world ready to work toward

something magical. This aspect of Rabb is captured beautifully in O’Brien’s

book, particularly in an extended appendix, which holds the notes of Le

Gallienne’s direction of “The Cherry Orchard” for the APA.

Rabb was hurt that O’Brien had fired him,

and he was often disparaging of the work that he was doing, savaging aspects of

“Two Shakespearean Actors,” a play directed by O’Brien that was then running on

Broadway. I ignored these rants, but I noticed that when an actor approached

our table and attempted to ridicule, in a similar manner, the work of Jack O’Brien, Rabb delivered a

coruscating peroration that left the man blanched and apologetic. “No one

attacks my friends,” Rabb told me, hoisting another drink.

It ended badly for Rabb, who would call me from

the Barbizon and ask me to bring booze “and maybe a boy?” he would add. I would

visit him, bloated and ruddy, unable to keep his robe around his body, asking

if anything I saw was of interest. Whatever his faults and whatever his demons,

he did not deserve the conclusion he got, one he would never have allowed and

would not have been able to stage. He would have required—and he needed--some

form of female deliverance.

Carrie Nye called a friend she shared with

Rabb one day in 1998. “I have bad news about Ellis,” she began. “Oh,” the

friend replied, “he’s in town? That’s bad news.” “No,” Nye told her, “he’s

dead.”

The female deliverance came when Carrie Nye

and Rosemary Harris, perhaps his closest female friends, battered but stalwart,

traveled to Memphis for Rabb’s funeral and acted as witnesses, friends,

artistic wives.

|

| A screen shot of Ellis Rabb and Carrie Nye in Maxim Gorky's Enemies (1973). |

O’Brien writes in this bracing book “Great

acting is always shockingly direct and simple, in the sense that love is.” So

is writing and so is living, and O’Brien does both directly and simply and

powerfully. This is a noble and painful book that resurrects Ellis Rabb and

places him both on a pedestal and in the center of our attention. I hope that

the next book does the same for Jack O’Brien. It is time now for his story.

© 2013 James Grissom

© 2013 James Grissom

Comments

Post a Comment

Thank you for your comments. The moderators will try to respond to you within 24 hours.